THE CRAFT

The art of sword making involves many crafts, each with its own particular challenges and rewards. The sword has always borne a strong relationship to the ideals of perfection and virtue. In the craft there is often a peculiar duality between the pursuit of a calculated form and finish and the immediate and sometimes surprising results that can emerge throughout the working process.

Perfection is a severe goddess, but however elusive perfection may be in the actual craft, it has to remain an influence; like gravity it pulls the maker towards the limits of skill, understanding and vision. There is, however, is a risk that while striving for control we may overlook the beauty that appears without invitation. Luckily, Perfection has a lovely twin sister named Harmony. Harmony’s gift lies in allowing us to discover beauty in the broken and the flawed through appreciating the proportion of all things.

Progressing to mastery in this craft also involves developing a deeper understanding of the subject, a personal attitude toward the work, and—whether it is realized or not—a personal philosophy of the craft. The work involves negotiating many kinds of limitations; even the tools and materials used impose finite concerns as much as they allow for solutions. The sword itself is defined by by millennia of history and tradition. Its quality as a weapon is determined by diametrically opposing aspects such as hardness and toughness, flexibility and stiffness, agility and stability. Together with the boundaries of perfection and harmony and the landmarks set out by function and tradition these limits provide contours to the chaos of creativity. Mastery may perhaps be understood as the ability to negotiate the gravitational pull of perfection, while balancing careful planning with an intuition for harmony. This is where much of the individual character in the work of any artist is born. The sword smith must relate to this if the work is to have integrity and value.

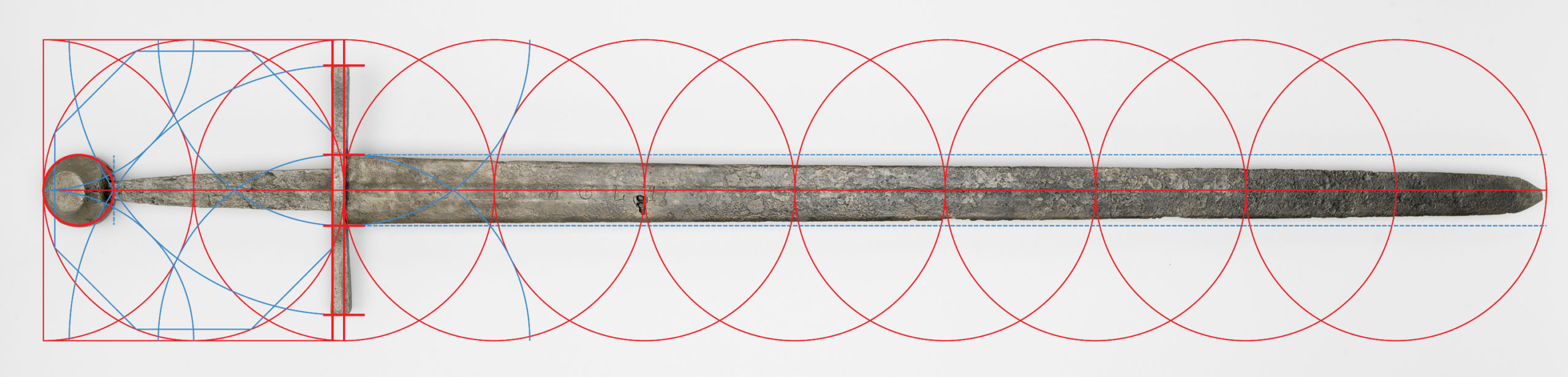

The making of these swords did not begin in the hot forge but in the cool storerooms of museums. Though time-less in character they follow principles for balance and function that has been revealed through hands on study of historical exemplars. Ancient swords were made with an interest for overall shape and proportions. The use of modular and geometric systems in their design has been an essential influence for the construction of the Reflections swords.

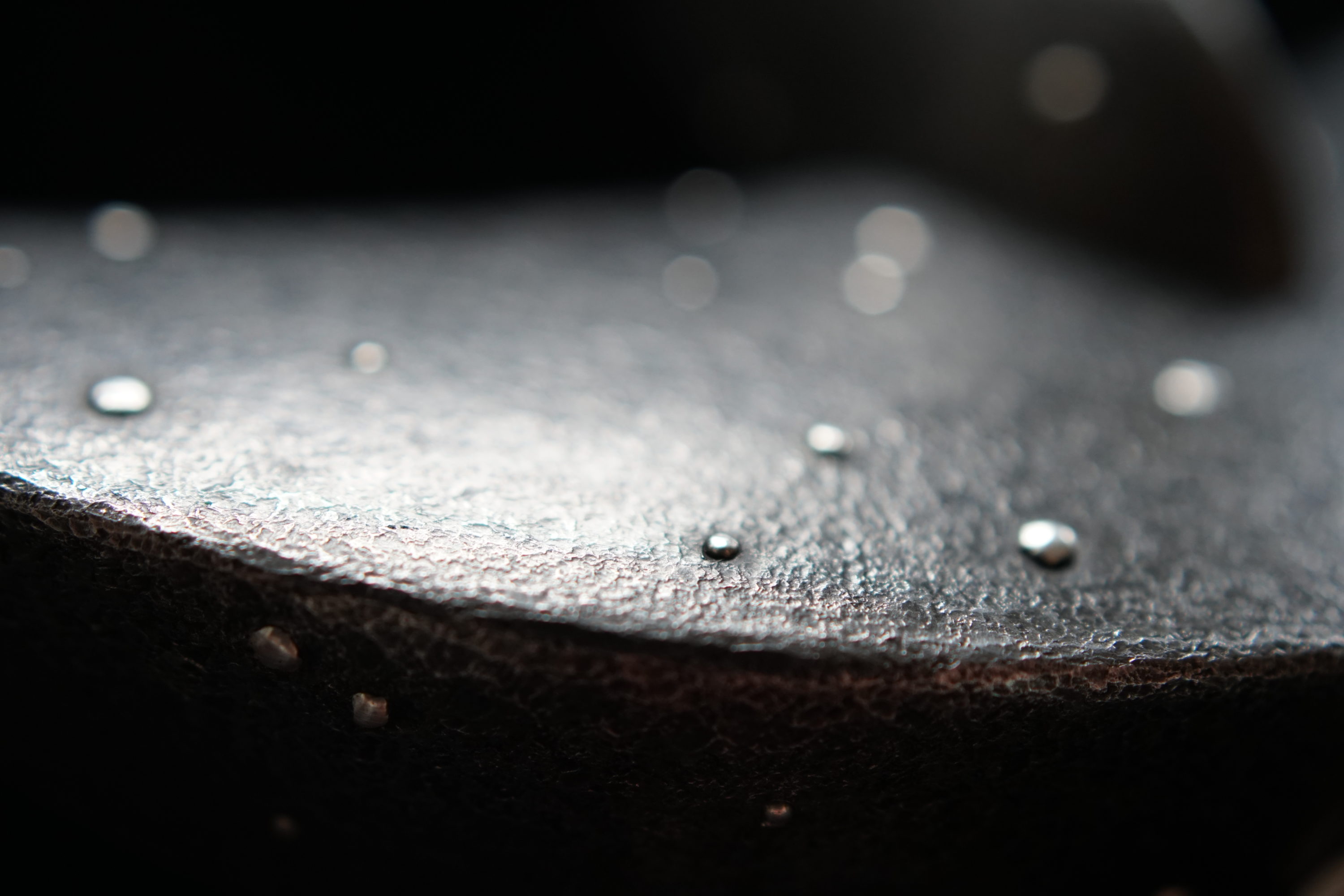

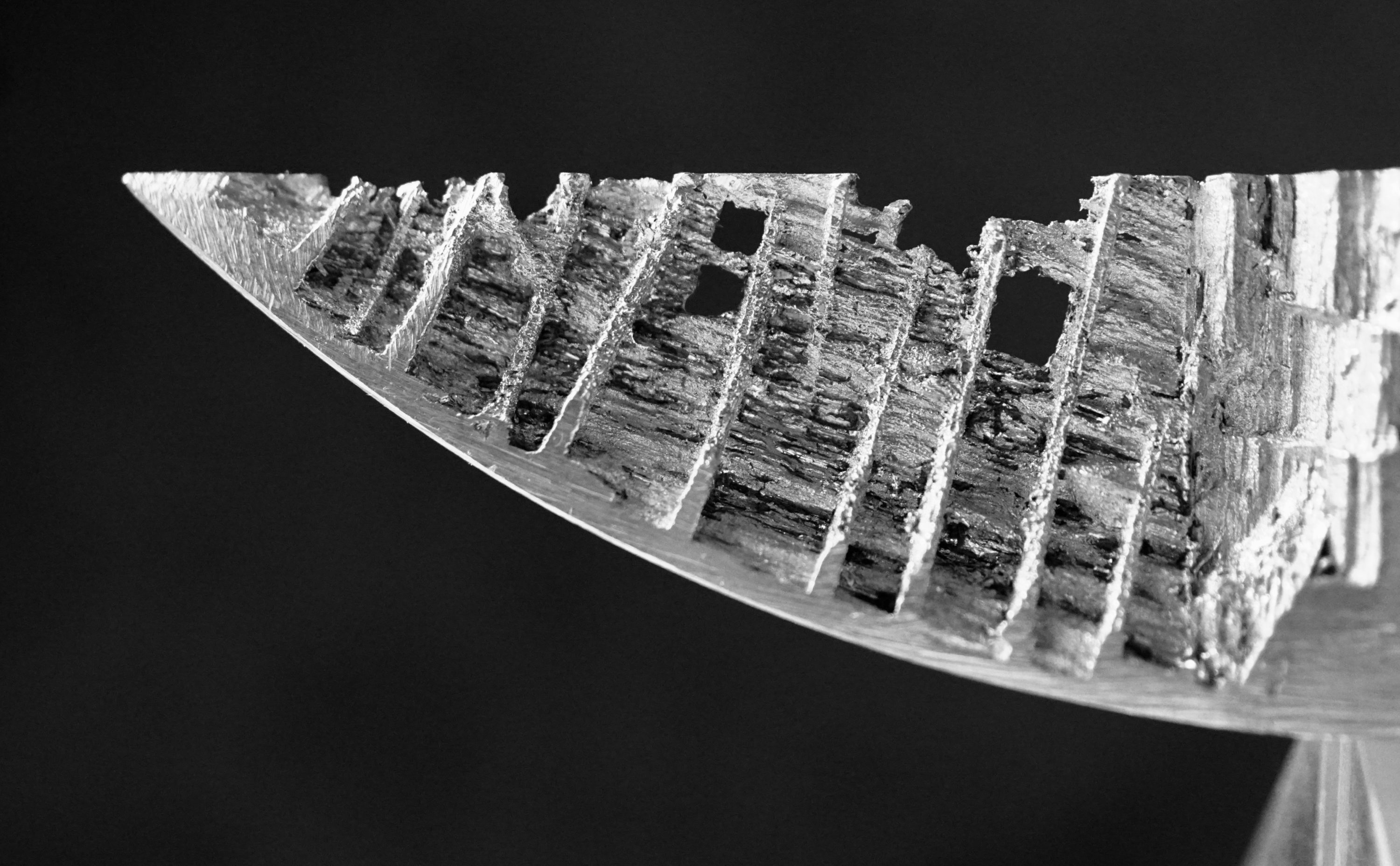

The transformation of materials through forging and heat treatment is central to the work of the sword smith. The blades of the Reflections swords are made from layers of different steels that are forge welded together at a temperature of around 1200 C° / 2200 F and further folded and manipulated into laminar structures. The resulting pattern reveal how the hammer blows have gradually brought shape to the steel. It also creates a chatoyance effect as light reflects on the thin, meandering layers that are revealed by etching and polishing in the final stage of the making of the blade. This is a trompe l´oeil illusion of three-dimensional peaks and valleys that seem to hover over the flat surface. These dancing reflections of light together with the carved undulating grooves add a sense of life or spirit to the otherwise severe and symmetrical form.

Once the blade is forged, hardened and polished, the other components of the sword can be created. Hilt components and scabbard mounts are sometimes forged, but also made through casting in bronze and silver. The hilts of the Fury daggers are created with a unique technique that was developed by the father of the artist.

Hilt parts and fittings are textured with specially prepared punches and hammers and sometimes through abrasion from sharp stones, and then patinated to bring out character and contrast. Gold and silver are used to add colour and highlights to the components using a range of decorative techniques such as keum-boo, fusing, koftgari and inlay. Garnets and meteoric iron are set in gold to strengthen thematic elements of the sword.

The making of a scabbard can demand just as much work as the sword itself. A core of laminated wood is lined with felt to protect the surface of the blade from scratching and reinforced with linen cloth on the outside. Over the textile wrap, a hard ground is built up and meticulously smoothed in preparation for 10 – 20 layers of lacquer. Alternatively, the scabbard is covered with leather that is subsequently embossed and stained for texture and colour, and finished with leaf gold decorations or other highlighting details.

The balance of a sword is always purposefully adjusted according to its specific design and intended use. Achieving a good balance is therefore involves more than simply adding a weighty pommel to act as a counterbalance. The blade itself must be made with a well-adjusted distribution of mass that makes for an agile and pleasing heft even before it is hilted. The gradual change in cross section and thickness from the base of the blade to the point is crucial in establishing the proper measures of stiffness and flexibility along its length. The hilt must provide the wielder with a good ergonomic control just as it fine tunes the dynamic properties of the sword so that it acts as an extension not only of the arm, but also of the mind.