DEDICATION

According to one tradition in ancient Greece, a daimon is a spirit that follows a person even from before the moment of birth and throughout their life. Daimons were thought to convey human things to the realm of the gods and to bring the divine to humans, as a kind of messenger or guide. Socrates described an inner voice who offered warnings, but never told him the correct path forward. Daimons could also be understood as a divine mode of action, a drive or a hindrance. The gods themselves were thought to act in secret as a daimon when interfering in the life of mortals.

The myths about the Olympians, the Titans and the lesser gods of ancient Greece are consistent in their core elements but vary greatly in their details. Each version of the story is a unique retelling of our shared human experience. We can understand them as complexes of cultural memes or emerging from archetypes of our psyche. They have survived by diffusing into and becoming part of cultures through millennia and are therefore more than just fragments of an ancient past; they form a heritage of ideas that provide a symbolic fuel that we use to describe who we are even today.

The gods of ancient Greece are very human in their temperament and appetites. Like us, they are neither good nor evil but rather a sum of their personal traits. Their strengths and flaws mirror our own, but writ large. In their exalted form they reflect our human nature. Their divinity embodies specific ideas, principles and elements that we also find within ourselves. Despite their power they are unable to act beyond their fixed role in the cosmos. Nor can they directly undo the act of another god even if they can change the outcome by granting favours or adding conditions. Thus, a minor god can sometimes cause difficulties for even the mightiest of the Olympians. Compared to the divine, mortal humans have in some ways a higher degree of freedom since we can act against our principles and overcome our own limitations in order to transform ourselves in acts of heroism.

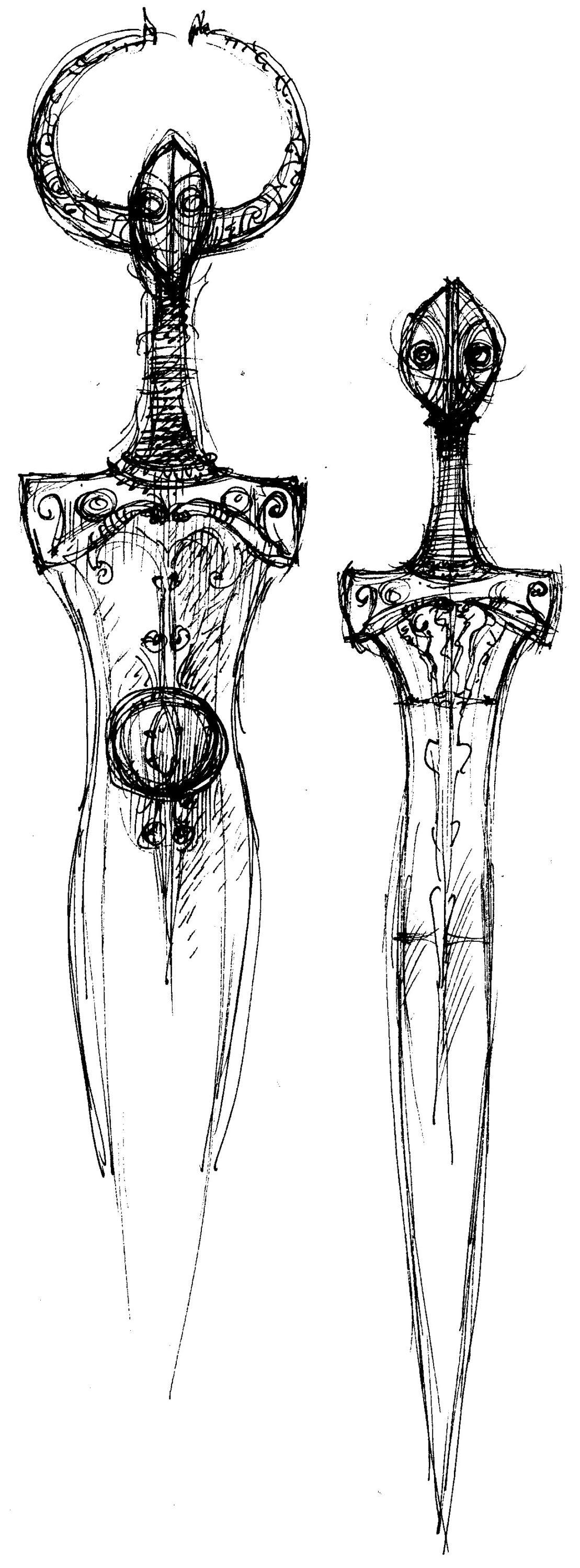

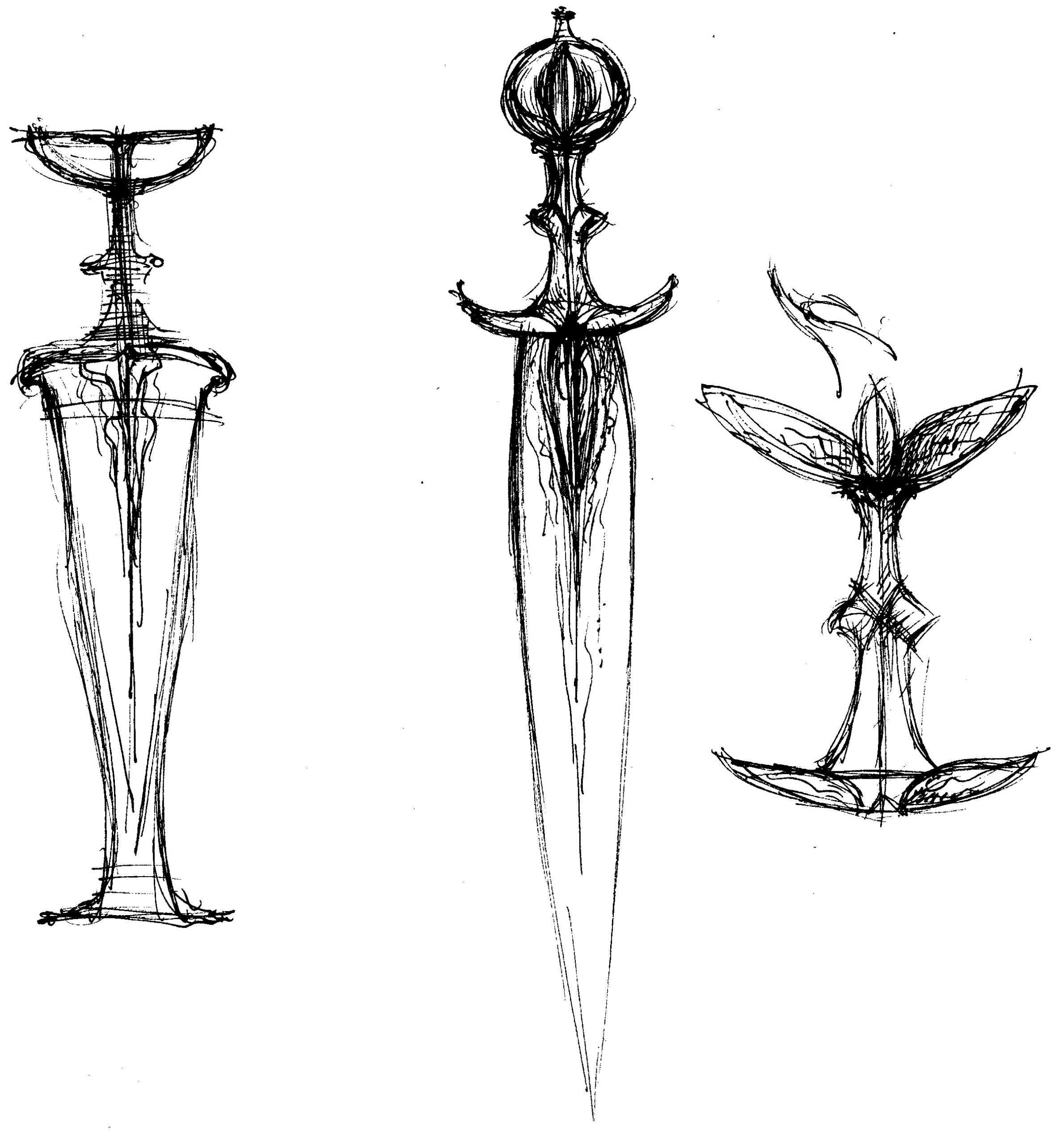

For our predecessors in ancient times it was common practice to offer votive gifts to the gods to mark transitions in life or to give thanks for providence and deliverance. Temples in antiquity were erected as votive buildings by the community and housed treasuries of gifts from grateful worshippers. Votive offerings were also made along with requests for future intervention. Children approaching adulthood would sometimes dedicate a lock of hair to symbolize their passage into a new phase of life. A retiring artisan might offer his tools to the gods in gratitude for a life well lived. Swords have a long tradition as votive offerings. For centuries, swords were dedicated in burials to follow warriors on their journey to the land of the dead. As the spoils of victory, they have been sacrificed in lakes, rivers and sacred groves in thanksgiving to gods of war. As works of art, they were devoted in celebration to the gods in holy places.

A votive offering is most fundamentally a gesture of dedication. The word dedication first appears in the 14th century as a name for the solemn act of consecrating something to a particular divinity or sacred use. Originating from Latin, the word did not take on its now familiar secular context untill hundreds of years later. What was once the act of making something sacred now refers more to an personal offering of loyalty or devotion to a cause, ideal, or purpose.

Dedication is intrinsic to craft. Without the discipline and engagement inspired by true dedication, the work will either be palpably hollow, or will not take shape at all. Dedication is also intrinsic to the sword. In times when people wielded the sword in defence of life, it served as a symbol and a focus for ultimate dedication; the sword represented explicit commitment to an idea, and a loyalty at the potential cost of life itself.

As humans we construct our identity and provide meaning to our interaction with the world by ascribing properties both to the sparks and the shadows of our mind and also to the objects that surround us. In this way, certain objects have a unique potential to carry meaning and thus the power to transform us and reveal our reality. The sword is such an object of power. It is an emblem of human conflicts over millennia, a defining hierloom of the mythical hero, and a symbol for our virtues and iniquities. To be bestowed a sword also means accepting new responsibilities. Becoming the owner of a sword involves a transformation of the individual, marking a new stage in life.

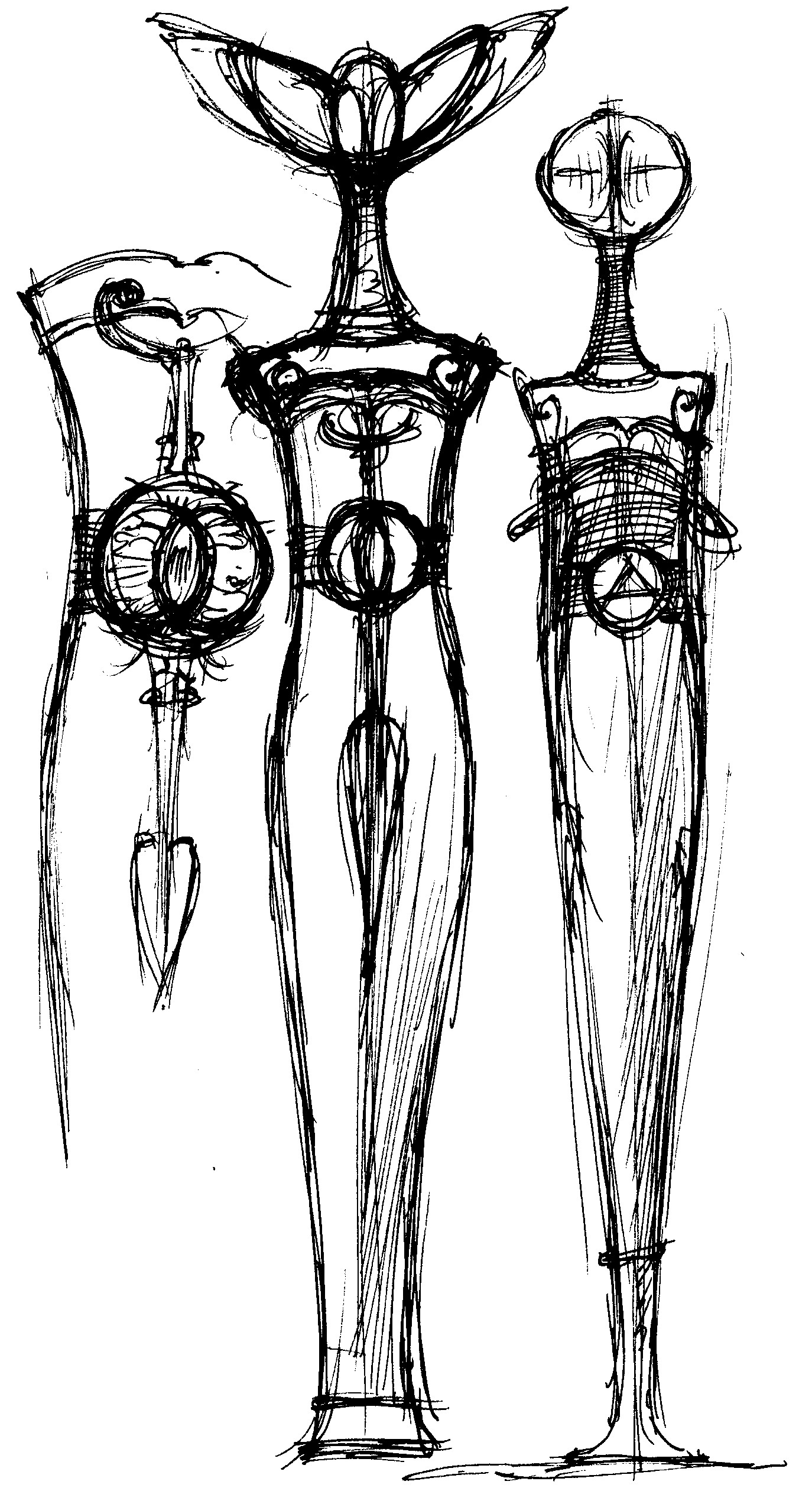

The making of these swords was a way to explore and relate to ideas of dedication, transformation and integrity, and an invitation to contemplate on the sacred principles that guide our lives. To fulfil this role as objects of power they had to be sharp, well balanced and purposeful but they must also be made with an aesthetic expression that leaves room for an individual to take on ownership and responsibility and thereby connect to an ancient goddess or daimon.